The following blog post is a summary of the article “Wildlife Crossings Can Mend a Landscape” by Anne Pinto-Rodrigues, published on February 21, 2024, in Sierra magazine. To read the original article, click here.

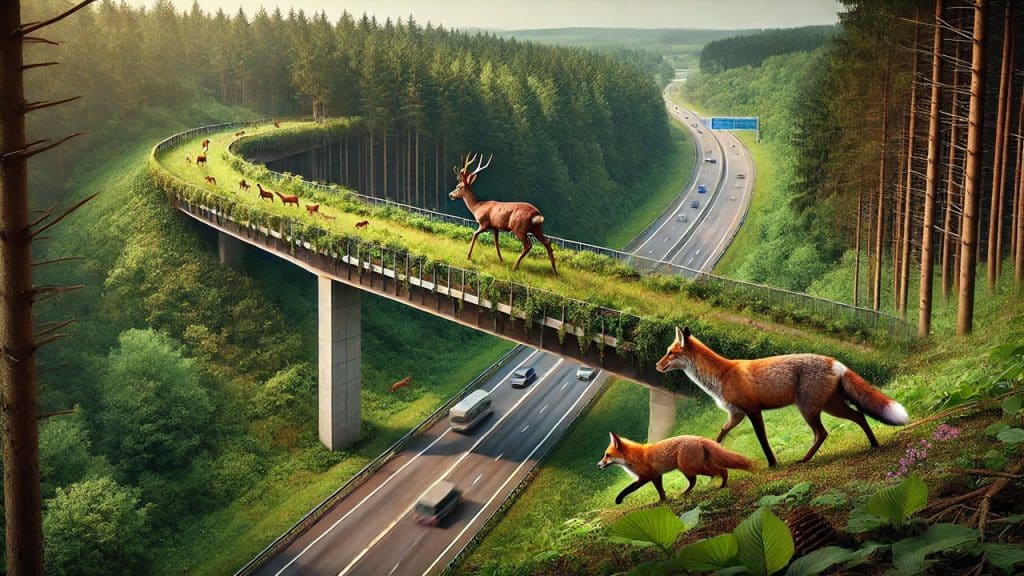

The Netherlands has made significant advancements in wildlife conservation through the development of wildlife crossings, such as the Zanderij Crailoo Nature Bridge, the longest of its kind in the world. These overpasses and underpasses allow animals to move freely between fragmented habitats without the risk of becoming roadkill. For over three decades, the country has prioritized reducing habitat fragmentation by constructing nearly 3,000 crossings, which cater to various species, from large mammals like deer and wild boars to smaller animals such as otters and hedgehogs. These crossings are crucial for species survival, providing access to food, mates, and new habitats, especially for endangered species. As one of the most densely populated nations, the Netherlands has been forced to address the severe impact of roads and railways on wildlife movement.

The country’s commitment to wildlife crossings began in 1974 with the construction of a badger tunnel and escalated with the 1990 Nature Policy Plan, followed by the 2005 nationwide defragmentation initiative known as the Meerjarenprogramma Ontsnippering (MJPO). The MJPO systematically assessed problematic locations and led to the construction of hundreds of crossing structures. Research by Dutch ecologists has demonstrated the effectiveness of these measures, with studies showing that roadkill of large mammals decreased by 83% when crossings were combined with fencing. Legal mandates, such as the requirement for environmental impact assessments (EIAs) in infrastructure projects, further ensure that wildlife protection remains a priority. Additionally, proper maintenance of these structures, such as clearing badger tunnels of water or trimming vegetation for butterfly-friendly overpasses, is essential for their continued effectiveness.

Other countries, including the United States, are beginning to adopt similar strategies, though progress has been slow. The U.S. passed legislation in 2021 allocating $350 million for a Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program, funding state and tribal authorities to develop habitat connectivity projects. However, experts like Marcel Huijser argue that defragmentation is not yet a priority in the country’s transportation planning. Unlike the Netherlands, where ecological concerns are institutionalized, many U.S. mitigation efforts have only succeeded due to legal battles or political power dynamics. A case in Montana, where tribal authorities halted a highway expansion until wildlife crossings were included, highlights the challenges of integrating ecological concerns into infrastructure projects. While progress is being made, experts emphasize the need for systematic planning and stronger commitments to wildlife conservation in the U.S.